Fighting ISIS and Learning Cyber-War

In November of 2016 USSTRATCOM authorized USCYBERCOM, then a component command, to begin executing offensive cyber operations against the Islamic State in support of Operation Inherent Resolve. The operation was given the name Operation Glowing Symphony, and the team responsible was Joint Task Force ARES. JTF-ARES was rapidly built from USCYBERCOM’s available Cyber Mission Force (CMF) teams for the express purpose of supporting OIR’s mission even before the command had reached full operational capability. The task force was directed to target Islamic State battlefield communications for intelligence collection and disruption in support of coalition troops on the ground as well as the terrorist organization’s use of social media. The operation is thought to be one of the largest, if not the largest, performed by USCYBERCOM and represents a landmark moment for the Department of Defense cyber-warfighting community.

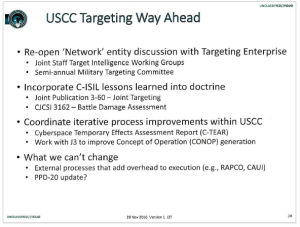

Around the same time Operation Glowing Symphony was approved for execution, the USCYBERCOM Joint Information Operations Center (JIOC) Combat Targets Division gave a top-secret presentation titled “Improving Intelligence Support to Cyber Operations”. The presentation, obtained by the National Security Archive via FOIA, is largely a discussion of the utility of the joint targeting cycle (as outlined in JP 3-60 Joint Targeting) to cyber operations but closes with a call to incorporate lessons learned from the counter-ISIS mission into joint targeting doctrine. This suggests that USCYBERCOM anticipated the significance of Operation Glowing Symphony to their growth as a cyber-warfighting entity such that it should impact the formation of joint doctrine.

Without public updates to JP 3-60 Joint Targeting, or CJCSI 3162 – Battle Damage Assessment, it is currently unclear how JTF-Ares and Operation Glowing Symphony have impacted joint doctrine. It is clear, however, that the counter-ISIS mission impacted how USCYBERCOM is approaching today’s challenges. General Nakasone, dual-hatted as both head of the NSA and commander of USCYBERCOM and the first commander of JTF-Ares when he was the commander of US Army Cyber Command, gave an interview to NPR last August in which he discussed how the formation of today’s Russia Small Group to combat the Kremlin’s information campaigns was guided by the formation of JTF-Ares. “So this concept of a task force lives on. A lot of that thinking came from what we were doing in 2016. It’s powerful to bring a number of different elements of a team together and be able to form something very rapidly to address a threat.”

There is a temptation to relegate the Operation Glowing Symphony chapter of cyber-warfare history to the “distraction” pile. It was, after-all, directed against a relatively unsophisticated adversary, undertaken by a still-developing force, and lacks publicly available success indicators. This would be a mistake, however. Operation Glowing Symphony gave USCYBERCOM their first “real-world” test on a problem that shares many traits with what large-scale cyber-warfare with a near-peer competitor may look like. Glowing Symphony was global in scale, required a significant degree of international coordination and deconfliction, involved coordination with kinetic operations in a manner that should inform how the US military approaches the cyber-enabled battlefield, and demonstrated the ability for USCYBERCOM to rapidly organize operational groups tailor-made to unique challenges like global terrorism or Russian influence campaigns. Operation Glowing Symphony was a watershed moment for US security capabilities and should be studied as such.

Michael Martelle is a research fellow with the National Security Archive’s Cyber Vault project.

(@MartelleMichael , @NSArchiveCyber)

By

By

Comments are closed.