The “Indiana Jones Warehouse:” How to use FOIA to get Documents from Purgatory

As documents age, the likelihood that they will be released to FOIA requesters should increase. But because of a quirk of the US record keeping system, this is often not the case. Usually, when someone requests a “historic document” (defined as older than 25 years) from an agency, the agency FOIA shop will state that it only deals with modern records, has found “no responsive records,” and is closing the FOIA request. Sometimes the agency will include language kindly suggesting that you conduct your search at the US National Archives (NARA).

But often these records are not at NARA either. NARA is up front in stating that only 2 to 5 percent of all federal records are deemed “permanently valuable historical records” and preserved for researchers at the Archives. But what it is less clear about is that there is a decades-long lag time between when these permanent historic records move from agencies to NARA –and that key historic documents can go to a “records purgatory” during these decades. If requesters do not know about this purgatory –the Washington Records Center– and the special steps needed to request records from it, they probably will be unsuccessful in many of their FOIA requests for records from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

In many respects, the Washington Records Center (WRC) is the real-life, US government equivalent to the warehouse where the Ark of the Covenant is stored, never to be found again, at the end of the Indiana Jones film, The Raiders of the Lost Ark. The Washington Records Center is located in a heavily guarded federal office park in Suitland, Maryland, encompasses 789,000 feet, and has the capacity to hold over 3.9 million cubic feet of federal records. Key government documents are stored in the difficult-to-access location, and the public –including many FOIA experts– doesn’t even know it exists.

Take a look at two confusing and conflicting FOIA regulations about records which may be at the WRC. The Department of State’s FOIA regulations state that “the Department ordinarily transfers records designated as historically significant to the National Archives when they are 25 years old. Accordingly, requests for some Department records 25 years old or older should be submitted to the National Archives.” There is no mention of the millions of State documents effectively hidden at the WRC.

To use a recent example, if a requester asked for documents from the State Department’s “country lot files” on Colombia during the early 1990s, State would respond with a “no records” response, and may tell you to go to look at NARA. (Troublingly, “no records” denials rise each year, and official DOJ FOIA statistics misleadingly do not count them as FOIA denials.)

But if a researcher went to NARA 2 to look for these lot files, they would not find them there either. Often, this is when researchers and FOIA requesters give up, thinking “perhaps these key documents I needed for my history really were destroyed.” There is a chance, however, that the documents are in purgatory, at the Washington Records Center. This is what the National Security Archive recently found, after successfully obtaining the State Department’s Colombia lot file. Unsurprisingly, searching for, and requesting documents from, the WRC is not exactly easy.

US National Archives regulations state, “NARA’s Federal records centers [including the Washington Records Center] store records that agencies no longer need for day-to-day business. These records remain in the legal custody of the agencies that created them. Requests for access to another agency’s records in a NARA Federal records center should be made directly to the originating agency. We do not process FOIA requests for these records.” One of NARA’s blogs, the FOIA Ombudsman, has recently elaborated: “What if an agency receives a FOIA request for an agency record that is being stored in an FRC? It is incumbent on that agency to contact NARA and request access to those records. That agency is required to review and process the records, and respond directly to the requester. NARA’s role is limited to assisting the agency with retrieval of the responsive records.”

But NARA’s processes generally do not work in practice. Agencies don’t keep records of the documents they have transferred to the Washington Records Center, so they will usually respond with an incorrect “no documents” response to FOIA requests. Likewise, the main NARA research facilities do not currently have a method of alerting researchers that the files they are seeking may be at the WRC.

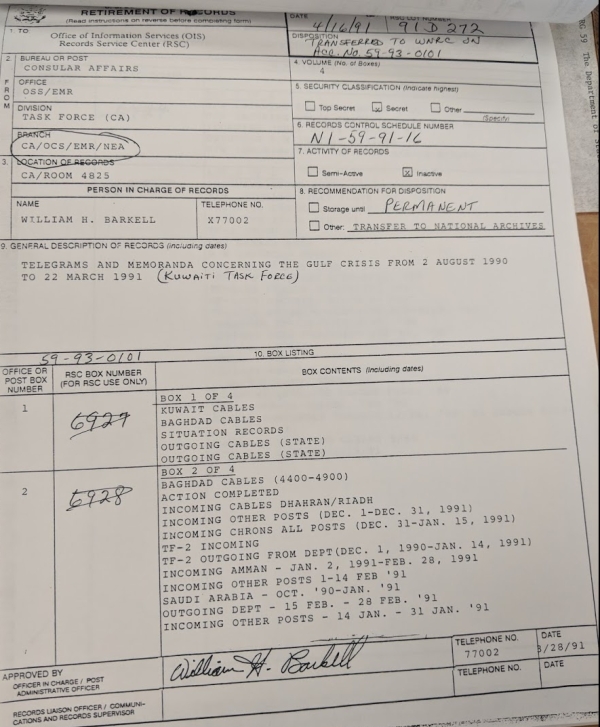

There is only one relatively convoluted process that gives researchers a fighting chance to force the release of documents held at the Washington Records Center. A researcher must schedule an appointment to visit the WRC, pass through one of the nation’s more onerous security checks, and view the SF 135 forms onsite. SF (Standard Form) 135s are the documents that agencies are required to fill out when they transfer records to the Washington Records Center. In theory, they are required to describe with some degree of specificity –to box or folder level– the documents they are transferring to the WRC. Once inside the WRC, researchers can easily view the SF 135s, organized chronologically by Record Group, with limited restrictions. Researchers can then use these documentary roadmaps to file FOIAs or MDRs to the originating agencies (not NARA) to free “recent historical” records from purgatory.

I recently had the opportunity to present some of my thoughts on the difficulty of getting access to documents held at the Washington Records Center to the Acquisitions & Appraisal and Records Management sections at the annual meeting of the Society of American Archivists. I was fortunate to have some back and forth with archivists, including some who worked at NARA and the WRC, after my presentation. Their position, as I understood it, was that they did a good job storing the records of agencies, as is their mandate; it was not the WRC’s fault if agencies weren’t searching the records stored there in response to FOIA requests.

Fair enough. But from the perspective of historians, researchers, and access to information advocates, the current status quo is not acceptable, and changes –on both the agency side and the NARA side– are needed to fulfill NARA’s mission to “drive openness, cultivate public participation, and strengthen our nation’s democracy through public access to high-value government records,” including the high-value documents at the WRC.

There are a number of steps that could be taken to fix this problem relatively easily.

- The comprehensive solution would be for NARA to end its policy of warehousing other agency records without having the authority to release them. (This policy would also benefit NARA proper, the Presidential Libraries, and the National Declassification Center). As is often pointed out, this would require proper funding of the Archives, a change to NARA’s regulations on records transfers (36 CFR Part 1235), and would possibly take a legislative tweak (probably to 44 U.S.C. 2107 and/or 2108), but as seen by recent legislation strengthening OGIS’s independence and improving the Presidential Records Act, there are certainly bipartisan allies on Capitol Hill who would support commonsense reforms that would allow citizens to access their historical records more easily.

- Short of this, DOJ OIP and OGIS, the agencies that oversee FOIA compliance, could undertake an effort to educate agencies on their responsibility to search records stored at the Washington Records Center, and ensure that they do so in a timely manner. DOJ OIP and OGIS should also review all new FOIA regulations to ensure they state clearly what records are stored at the WRC, how requesters can access them, and the agency’s procedures for efficiently searching WRC records.

- NARA is also not entirely off the hook. A vast quantity of the records at the WRC actually should be in the stacks of the National Archives. What is NARA doing to ensure that the documents move efficiently from the WRC to NARA, from purgatory to heaven?

- It is also far from clear that NARA’s procedures and policies used by agencies to search the documents at the WRC after they are requested via FOIA are efficient.

- Even if nothing else changes, it is anachronism that potential researchers have to drive to Suitland, Maryland to see the index of the files held at the WRC. At a minimum NARA and agencies should be required to post all future SF-135 forms online. (This has been suggested at Federal FOIA Advisory Committee meetings, but not acted upon.) Additionally, NARA should seriously consider a project to digitize and post all SF-135s in its collection, so that the public can know which records are theirs. The reward would likely be worth the work.

In the meantime, historians, researchers, and requesters hoping to access records from several decades ago will have put this line in all of their FOIAs, MDRs, and appeals: “As you know, your agency is required to search the records stored at NARA’s Washington Records Center in Suitland, MD, but still technically under your agency’s control. For more information see 36 CFR 1250.8,” and utilize the onerous SF-135 process.

As Indiana Jones once said, “the SF-135 marks the spot.”

Comments are closed.